The intricate dance of learning and memory within the human brain represents one of neuroscience's most captivating subjects. For centuries, philosophers and scientists alike have pondered the mechanisms that allow us to acquire new information, store it, and recall it at will. Today, cutting-edge research continues to peel back the layers of this complex process, revealing a sophisticated neural architecture governed by precise biological rules. The journey from a fleeting thought to a lasting memory involves a symphony of electrical impulses, chemical signals, and structural changes at the synaptic level, all working in concert to shape our understanding of the world and ourselves.

At the heart of learning and memory lies neuroplasticity, the brain's remarkable ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. This adaptability is not merely a passive response to experience but an active, dynamic process that underpins our capacity to learn. When we encounter new information or experiences, specific patterns of neural activity are triggered. Repeated activation of these patterns strengthens the connections between neurons, a phenomenon famously encapsulated by Canadian psychologist Donald Hebb's axiom: "Neurons that fire together, wire together." This Hebbian plasticity is the foundational principle upon which contemporary models of memory formation are built.

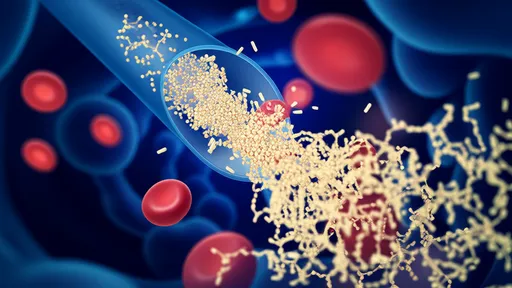

The primary cellular mechanism believed to be the cornerstone of memory formation is Long-Term Potentiation (LTP). First discovered in the hippocampus, LTP refers to a long-lasting enhancement in signal transmission between two neurons that results from their synchronous stimulation. It is essentially a physiological record of experience. When a presynaptic neuron persistently stimulates a postsynaptic neuron, the synapse between them becomes more efficient. This efficacy is often achieved through the increased release of neurotransmitters like glutamate and the amplification of receptor density, particularly NMDA receptors, on the postsynaptic membrane. LTP is not a monolithic process but varies in duration and mechanism, providing a versatile toolkit for encoding memories that last from hours to a lifetime.

While LTP strengthens connections, its counterpart, Long-Term Depression (LTD), plays an equally vital role by weakening synaptic efficacy. This might seem counterintuitive for memory, but it is crucial for refining neural circuits. LTD eliminates unnecessary or outdated connections, preventing neural networks from becoming saturated and allowing for new learning. This delicate balance between LTP and LTD ensures that our memory systems remain efficient, adaptable, and capable of continuous updating, much like pruning a tree to encourage healthy growth.

The physical trace of a memory, known as the engram, is believed to be stored within the populations of neurons and the specific synapses that were active during the initial learning event. Modern techniques, such as optogenetics, have allowed researchers to not only identify these engram cells but also to manipulate them—artificially activating them to trigger recall or suppressing them to induce forgetting. This work has moved the engram from a theoretical concept to a tangible biological reality, demonstrating that memories are physically inscribed in the brain's circuitry.

Memory is not a unitary faculty but is composed of multiple systems. The most fundamental distinction is between declarative (explicit) memory and non-declarative (implicit) memory. Declarative memory, which involves the conscious recall of facts and events, is highly dependent on the medial temporal lobe, particularly the hippocampus. The hippocampus acts as a central hub, binding together the disparate elements of an experience—sights, sounds, emotions, and context—distributed across the cortex into a coherent memory. Over time, through a process known as systems consolidation, this memory becomes increasingly independent of the hippocampus and is stored more permanently within the neocortex.

In contrast, non-declarative memory operates unconsciously and includes skills, habits, and conditioned responses. This form of memory relies on structures such as the basal ganglia, which is critical for habit formation, and the cerebellum, which is essential for motor learning and coordination. The amygdala also plays a specialized role, particularly in the formation of emotional memories, by modulating the strength of storage in other brain regions. This multi-system architecture allows the brain to efficiently process and store different types of information using optimized neural pathways.

Consolidation is the process that transforms a fragile, newly formed memory trace into a stable, long-lasting state. This process occurs in two main phases: synaptic consolidation and systems consolidation. Synaptic consolidation, which happens within minutes to hours after learning, involves the synthesis of new proteins that stabilize the synaptic changes initiated by LTP. Systems consolidation, on the other hand, is a much slower process, taking place over weeks, months, or even years, as the hippocampus gradually transfers memories to the neocortex for long-term storage. Sleep, particularly slow-wave sleep and REM sleep, has been shown to be critically important for both forms of consolidation, actively replaying and strengthening the day's memories.

The ability to access stored information, or recall, is itself a reconstructive process. Recalling a memory does not simply involve playing back a perfect recording; instead, it often requires the hippocampus to reactivate the distributed cortical patterns that represent the memory. Each time a memory is recalled, it becomes labile and susceptible to modification before being re-stabilized through reconsolidation. This provides a vital mechanism for updating memories with new information but also makes them potentially vulnerable to distortion.

Understanding the neural basis of learning and memory has profound implications for addressing neurological and psychiatric disorders. Conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, which devastates memory, are characterized by the degeneration of key regions like the hippocampus and the entorhinal cortex. Research into LTP, LTD, and neuroplasticity is driving the development of novel therapeutic strategies, from drugs that modulate neurotransmitter systems to non-invasive brain stimulation techniques aimed at enhancing cognitive function. The future may even see therapies that can directly manipulate engram cells to restore lost memories or alleviate the traumatic recall seen in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

In conclusion, the neural foundations of learning and memory form a vast and intricate landscape, woven from the threads of cellular change, systemic interaction, and molecular biology. From the silent strengthening of a single synapse through LTP to the grand, brain-wide reorganization during systems consolidation, each step is a testament to the brain's extraordinary capacity for change. As research technologies advance, allowing us to observe and influence these processes with ever-greater precision, we move closer to unlocking the full potential of the human mind, not only to understand how we remember the past but also to shape how we learn in the future.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025